Full Forecast for the Global Economy in 2024–2025

Genevieve Signoret & Delia Paredes

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

Read the main takeaways here, the full report here, and consult the forecast tables here.

Momentum

Inflation rates have continued to come down in the United States, even as nominal GDP, which is the sum of all income in the economy, continues to soar. On a three-month-over-three-month basis in December, core PCE inflation hit the Fed’s target in December 2023, and, in January, at 2.1%, came close. Yet the Fed is signaling that it probably won’t cut rates in March. Why?

Driving Fed reluctance to cut are strong household demand for goods and services and strong business demand for labor.

Markets are listening to the Fed, finally. Whereas the federal fund futures prices used to imply a 84% probability of a March Fed rate cut at the end of last year, an 100% probability of one in May, and altogether seven cuts in 2024, at the time of writing, they were signaling that market participants are practically ruling out a March cut, see a mere 30% probability to a rate cut in May, and anticipate only three cuts in 2024, the same number that, per their dot plot, FOMC members themselves anticipate. Market outlooks and those of the Fed are in sync at last.

At the same time, the U.S. Treasury is having to issue massive amounts of debt and is projected to shift its composition of issuance this year out farther on the yield curve than before. If it does, it will exert upward pressure on long-term bond yields from the supply side. Likely exacerbating the upward pressure from the demand side today is the fact of (so far) continuing quantitative tightening (QT).

Despite Fed hawkishness relative to prior market expectations, consequent upward revisions in market expectations as to the path of short-term rates, announcements that a gush of long-term Treasury supply will soon flood the market, and continuing QT, rates have come way down from their October peak of nearly 5% to around 4%. Possibly contributing to that drop is the expectation that the Fed will start tapering QT this year. A tapering off of QT translates to stronger demand for bonds and resulting downward pressure on rates.

Three Scenarios

We hold to our view from last quarter that what path the economy is on depends on where long-term rates will move. Last time, we posited two scenarios. In Soft Landing, disinflation slows down, keeping the Fed hawkish enough to hold rates steady in quarter one. These projections have borne out so far. Where we were off, however, was for growth, which we saw slowing down already in late 2023, and unemployment, which we saw rising to 4.1% in early 2024. Real GDP grew at an annual 3.0% rate in Q4 2023, and, by February, the unemployment rate was still at only 3.9%. These data throw our former base case into serious question.

We now see three possibilities:

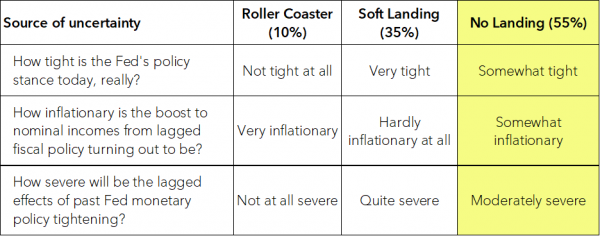

- No Landing. In this, our new base case, the economy does not land during the forecast period. We assume that the lagged effects of past Fed monetary policy tightening that still lie ahead will be only moderately severe. Also, that Fed’s policy stance remains somewhat tight, a stance that, given lingering inflationary pressures from the lagged effects of Covid-era fiscal stimulus, is appropriate. Our conviction is weak: we assign to No Landing a subjective probability of only 55%.

- Soft Landing. In this our former base case, the elusive landing does come, and in fact lies just around the corner. The Fed’s policy stance is assumed to be quite tight, fiscal stimulus to be running out, and the sole reason we haven’t seen the landing yet to be that monetary policy acts with a longer lag than we had thought. While still plausible, this scenario is seeming less and less likely. We hereby ditch it as our base case, slashing the subjective probability we assign to it to 35% from our previous 65%.

- Roller Coaster. This is our downside risk scenario. Monetary policy is assumed to be not tight at all—just look at the stock market! Also, Covid-era fiscal stimulus is assumed to be inflating the economy still, whereas past monetary tightening is seen as having almost entirely worn off. The economy is dangerously hot by this view, so hot that inflation is about to re-surge. To combat it, the Fed ends up having to raise rates so high that it sends the U.S. economy into a recession next year. We assign a low 10% subjective probability to this scenario.

We summarize our three scenarios in the following set of pivotal assumptions:

Assumptions That Distinguish Across our Global Macro Scenarios

Source: TransEconomics.

We have built these three divergent scenarios on a single foundation, a set of assumptions whereby we assume away tail risks:

Assumptions Common to All Our Global Macro Scenarios (Exercise by Which We Assume Away Tail Risks)

- The Gaza War will not lead to direct military involvement by Iran.

- No new pandemic will break out.

- War will not break out over the Taiwan Strait.

- No cyber terror attack will paralyze the world economy for an extended period.

- No major world leader will be assassinated.

- Trump will not trigger a constitutional crisis.

- AMLO will not trigger a constitutional crisis.

- It will take China several years to resolve its twin debt crises.

- Putin will stay in power throughout the forecast period.

- The Russia–Ukraine War will persist throughout the forecast period.

Forecast, Narrated

In all three scenarios, the dreaded slowdown in the United States begins at last in the second half of this year, driven by the lagged effects of monetary policy and in particular high interest rates. Households start to fall behind on auto and consumer debt payments. And corporations and real estate operators run into trouble refinancing maturing credit obligations taken on when rates were at rock bottom.

What varies across the scenarios is the severity of the slowdown and whether inflation re-surges before the slowdown even begins.

No Landing

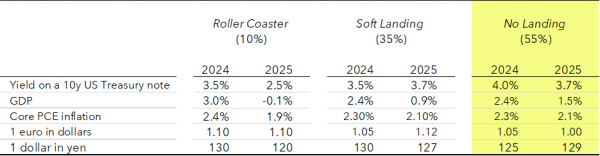

In our central scenario, No Landing, the slowdown that begins in quarter three of this year never becomes so severe as to merit the moniker Landing. And U.S. growth continues to surprise so much to the upside in the first half of the year that the Fed, rather than cut rates in quarter two as many expect, postpones its first cut to July. During quarter three, the Fed cuts rates twice, each time by a quarter percentage point. Then it does so again in the winter. Meanwhile, inflation has hit the target but seems perpetually more likely to rise above it than fall below it. As a result, the Fed stops at 4.75%.

Soft Landing

Soft Landing used to be our base case. In contrast to No Landing, disinflation is faster and more sustained than in No Landing, and signs of the slowdown the slowdown that begins in quarter three of this year is abrupt and severe. The Fed cuts rates all the way to 3.50%.

Roller Coaster

We continue to see Roller Coaster, first introduced last quarter, as plausible but unlikely. In Roller Coaster, strong nominal income from lagged Covid-era fiscal stimulus drives growth to accelerate in quarter two and core PCE inflation—the Fed’s favorite metric—to reverse course in April–May and re-surge a bit. This leads the Fed to make a mistake. Thinking their hard work has been undone and inflation is about to blow up out of control, it hikes its policy rate one more time in June to 5.75 and keeps them there for six months. This drives the economy over the cliff into a recession.

Our three scenarios, summarized

Source: TransEconomics.

We encourage readers to consult our full set of forecast tables in the Appendix.