ECB enlarged QE, Selic +50bp, BoE achieved unanimity

Genevieve Signoret

Policy

The European Central Bank (ECB) enlarged its quantitative easing program to include sovereign bonds and made it open ended. Mario Draghi—the ECB president—announced that the ECB will buy €60Bn worth of government bonds, asset-backed securities and covered bonds every month until at least September 2016. The extended program will start in March. Markets were pleasantly surprised: whereas they expected a €500Bn program, the ECB delivered €1.1Tn one, and an one that’s open ended in the sense that the ECB will carry out this program until “until the Governing Council sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation that is consistent with its aim of achieving inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.” We expect the ECB’s program extension to prevent the euro area from falling into a deflationary spiral.

During the press conference, Mr. Dragui emphasized that 20% of the asset purchases will be subject to a regime of risk sharing while the risk of the remaining 80% will be absorbed by National Central Banks (NCB):

With regard to the sharing of hypothetical losses, the Governing Council decided that purchases of securities of European institutions (which will be 12% of the additional asset purchases, and which will be purchased by NCBs) will be subject to loss sharing. The rest of the NCBs’ additional asset purchases will not be subject to loss sharing. The ECB will hold 8% of the additional asset purchases. This implies that 20% of the additional asset purchases will be subject to a regime of risk sharing.

Richard Barley from the WSJ mentioned that the lack of risk sharing might cause the investors to fear they can become subordinated creditors in the case of a default:

If a national central bank suffered losses and needed to be recapitalized by its government, and risk isn’t shared across the eurozone, private bondholders could take a bigger hit to bail the central bank out, UBS notes. They would implicitly bear the cost of recapitalization. This was a key problem with the ECB’s previous foray into government bond markets: investors feared they would become subordinated creditors. ECB purchases caused investors to revise up their assumptions of losses given default, making them reluctant to hold bonds. But since default risk now appears low, this is less of a problem.

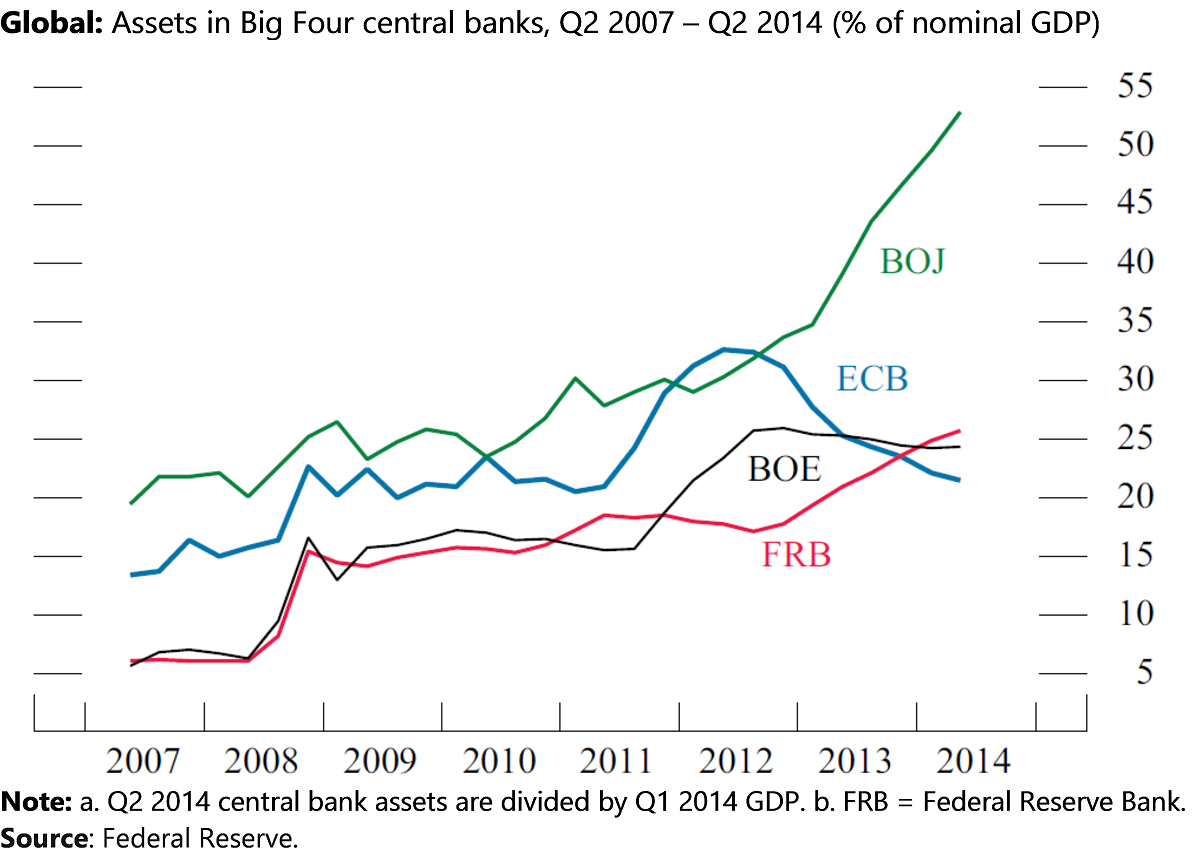

The ECB’s balance sheet has been shrinking since 2012

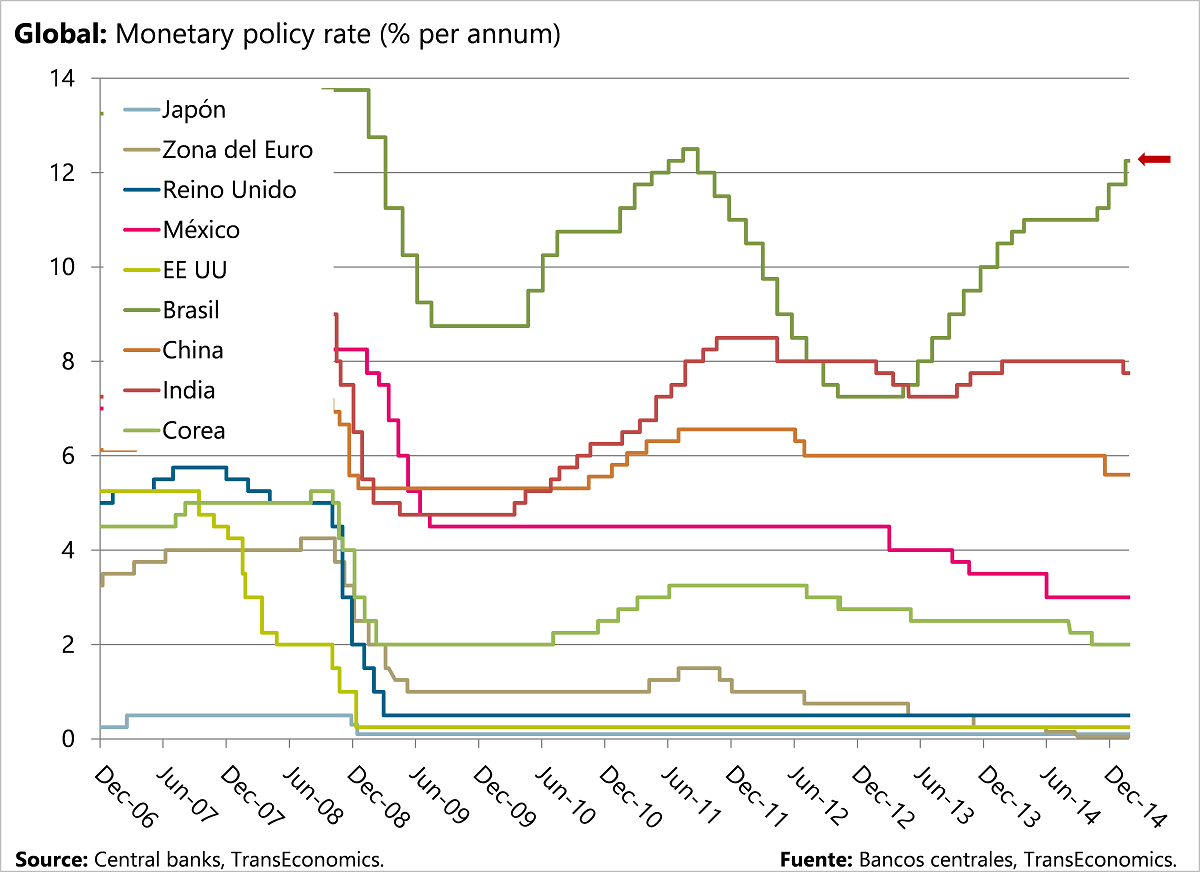

The Bank of Brazil continued its tightening cycle with a 50bp increase in its monetary policy rate to 12.25%—its highest level since 2011. Inflation is still high and growth low in Brazil. This week, Joaquim Levy—Brazil’s new finance minister—announced tax increases on fuel and loans to individuals to help balance the government’s budget deficit. More fiscal discipline in Brazil would bring interest rates down. Currently and traditionally, the central bank has alone borne the burden of fending off or battling inflation.

The Bank of Brazil continued its tightening cycle with a 50bp increase in its monetary policy rate to 12.25%

The Bank of Japan maintained unchanged its quantitative easing program. It lowered its real GDP growth estimate 2014 but revised up its projections for 2015 and 2016. It lowered its core CPI projection for 2014 to 0.9% (excluding impact of VAT hikes) and 2015 to 1.0% while raising it marginally for 2016 to 2.2%.

The Bank of England minutes last week showed that Martin Wheale and Ian McCafferty—the two hawkish dissenters of previous meetings—had realigned themselves on January 8 with the majority backing up an unchanged monetary policy stance.