Still Soft – Momentum

Genevieve Signoret

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

The following is an excerpt from Quarterly Outlook. Click here to read the full report.

Momentum

Stagflation and negative supply shocks

The world economy is experiencing stagflation: a situation in which output is contracting and inflation rates have moved higher.

Output is contracting

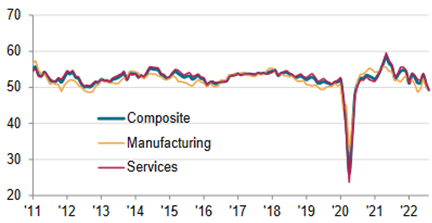

Global Composite Output, Manufacturing Output, and Services Business Activity Index, sa, >50 = growth since previous month

Source: J.P.Morgan, S&P Global.

Consumer prices are accelerating

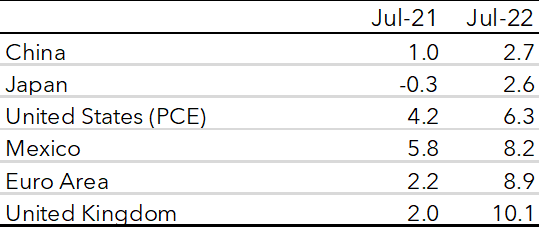

Selected countries, Annual July 2022 12-month inflation rates (%)

Source: Bloomberg.

The predominant root cause of this stagflation is a cascade of negative supply shocks. A negative supply shock is any event that causes output at every price to be reduced.

An example is a public health crisis such as a pandemic that causes production shutdowns. Another is a drought, for example one induced by climate change. A third example is war.

Do you see now why we speak here of a “cascade” of supply shocks?

Now, supply scarcities that follow from a negative supply shock drive up prices. When the economy is left alone, it is this inflation that gets demand and supply automatically into balance. Prices, then, are the signals of scarcity that, barring policy intervention, restore the balance between supply and demand [1]. If central banks can tolerate the higher inflation (for example, because they think it’s likely to be transitory) so they leave the price system to do its work—signal those scarcities and thus get demand and supply back in balance—yes, less is produced and sold than before, but prices and wages have moved up, so incomes can stay intact. Profits are preserved. People keep their jobs. People keep up with their debt service. And public treasuries remain flush. Negative supply shocks, then, do not inevitably lead to a recession.

If, on the contrary, central banks cannot tolerate the inflation resulting from the supply shocks and thus decide to intervene to restore the balance between supply and demand by suppressing demand through monetary tightening, profits will shrink or disappear, jobs will be lost, debt payments will be missed, and tax revenues will come down. In other words, a recession will ensue.

Central banks have had it with high inflation

Today, central banks cannot tolerate the inflation brought on by supply shocks. The cascade of shocks has gone on for too long: first Covid, then the Russian invasion of Ukraine, then droughts, and now Covid aftershocks (supply chains, labor participation rates not yet back to their pre-Covid levels, and recurring shutdowns in China).

Supply chains are still not completely repaired

Global Supply Chain Pressure Index since 2016 (standard deviations from average value)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Labor force participation rates in Europe (not shown) and the USA have yet to recover

U.S. Labor participation rate, last 10 years (% of working age population)

Source: FRED.

Central bankers fear that they’re going to lose their hard-won credibility as to their capacity to get inflation rates back to their targets. So they’re going prioritize the safeguarding of their inflation-fighting credibility over the safeguarding of people’s jobs. And we are going to assume in all three of our scenarios that central bankers will remain single-mindedly fixated on preserving this credibility throughout the eight-quarter forecast period. No central bank during this forecast period will tolerate inflation rates any higher than targeted any longer; hawkishness is the universal order of the day.

We do anticipate wide variations in the severity of outcomes. In particular, we expect that the United States economy will do less badly than most. This is because, in our view, inflation in the United States is being driven not only by negative supply shocks but also by some positive demand shocks—namely, massive stimulus during Covid and long delays in removing it.

Covid stimulus was massive

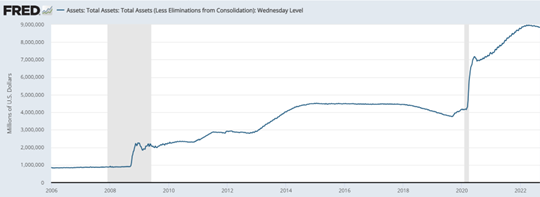

Federal Reserve total assets, since 2006 (millions of dollars)

Source: FRED.

The Fed’s start to the removal of Covid stimulus was long delayed

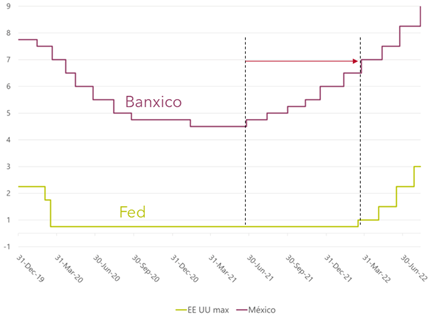

Monetary policy rate, Banco de México and Federal Reserve, since 2019 (% per annum)

Source: Bloomberg.

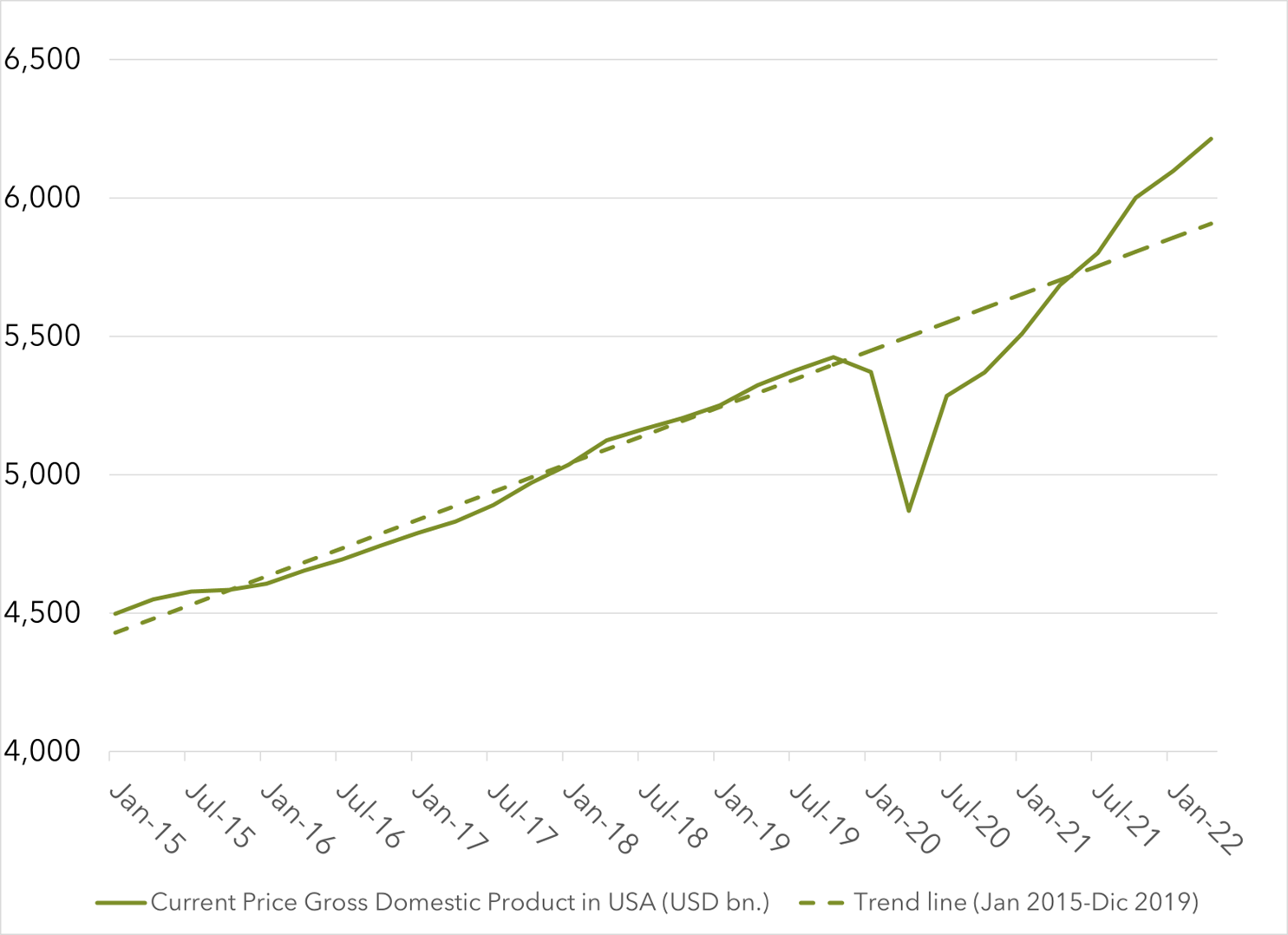

These shocks have pushed total U.S. income, measured by nominal GDP, onto a path that has deviated from its pre-Covid trend, crossing it from below.

In the US, demand-side stimulus during Covid blew total income off track

U.S. nominal GDP since December 2014 (billions of dollars)

Source: FRED.

[1] For an excellent exposition of this concept, see George Selgin’s Less Than Zero.