Don’t shoot the piano player, part 2: how did central bankers err?

Alastair Winter

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

This is the second of four related entries by Alastair Winter. For relevant background to this article, please see his preceding article, Don’t shoot the piano player, Part 1: central bankers under fire.

Yesterday we ended our piece with the question, can it be a coincidence that none of Messrs. Powell or Bailey or Ms. Lagarde is an economist? Professor Ricardo Reis of the London School of Economics most definitely is an economist, and he has been making waves since June with his paper ‘The Burst of High Inflation in 2021–22: How and Why Did We Get Here?’.

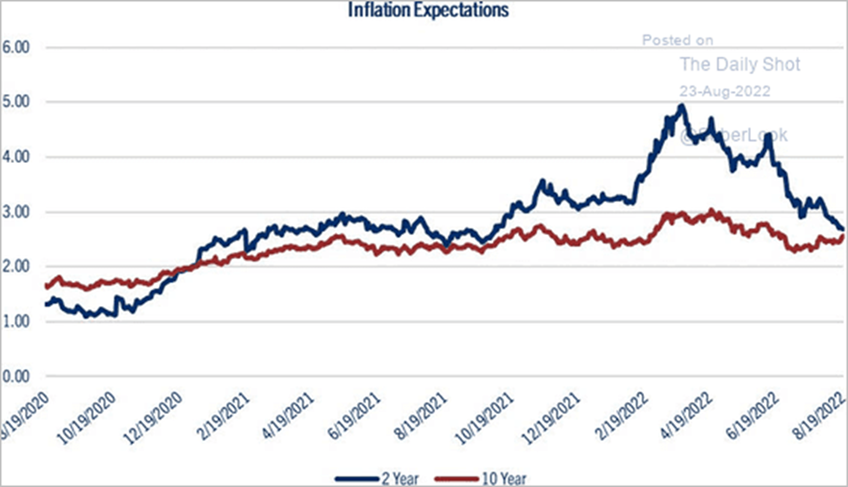

Professor Reis sets out four ‘hypotheses’ that explain the surge in inflation, each of which he deems a mistake on the part of the central banks. Looking at Figures 1 and 2, it is hard to disagree with him. His is an academic paper, nevertheless, so what follows is my attempt to describe in lay terms what, in his view, the mistakes made by central bankers over the last two years:

- 1. An underestimate of the inflationary impact of A, the pandemic supply and demand shocks, B, the official measures taken to support businesses and households, and, C, the rise in energy prices during 2021.

- Failure to allow for the possibility of an abrupt shift in inflationary expectations.

- Overconfidence in the idea that monetary policy can achieve growth free from inflation, a cockiness bred by the two prior “highly successful” decades.

- Taking low bond yields as a vote of market confidence in their reluctance to hike rates.

Figure 2: Central banks were caught off-guard in 2021

Source: John Lynch, Comerica Wealth Management

Professor Reis formulates his hypotheses within the conventional framework that monetary policy can control inflation, albeit not perfectly and with mistakes made for good reasons as well as bad. On that basis, he comes to the damning conclusion that the central banks have chosen to allow inflation to exceed their targets—2% per annum for each of the Bank of England (BoE), European Central Bank (ECB) and Fed. This is potentially lethal ammunition for those who would shoot the “piano players”.

Writing as a non-academic observer, I cannot help but see in all four Reis hypotheses a fundamental problem that dates back a lot further than 2020. For too long. central bankers have claimed to be in control of their respective economies. This has made them complacent about inflation, which has indeed been relatively subdued since the 1990s but for reasons other than masterful monetary policy. That complacency has in turn led them to pay more attention to boosting economic growth and thus be reluctant to tighten monetary policy even when it’s apparent that inflationary pressures are building.

Overconfidence has led central bankers also to adopt measures such as huge asset purchase programs and indefinite periods of Zero (or Negative) Interest-Rate Policy despite their uncertainty as to the long-term effects.

However grave their mistakes over both the short and long term, it would seem only to make matters worse to shoot (metaphorically) these erring “piano players”. The positions of the Fed and ECB are constitutionally unassailable and the tenures in office of Mr. Powell and Ms. Lagarde secure enough. The BoE’s status is less clear given the stakes raised over a review of its mandate by a government willing to use its Parliamentary majority to overturn or circumvent established practices (and laws).

Meanwhile, Governor Bailey insists that he and his colleagues are “doing the best they can” in the face of unforeseeable and uncontrollable external developments. The sterling would be (already is?) the most likely first casualty of any threat to BoE independence, while the foreign investors who hold 30% of gilts in issue will want to conduct (already are conducting?) reviews of their own in the light of any such threat.